Citizen Science in Your Own Backyard

If you have ever been interested in observing a bird building a nest outside your window, citizen science could be for you. If you have ever wondered what the best time to plant your snap peas is, you could be a citizen scientist. If you have ever been curious about how long it takes a yellow dandelion flower to turn into a white puffball, you could be a citizen scientist.

Citizen science, also known as crowd-sourced science, is the collection of data related to nature by members of the public. Because professional scientists can’t be everywhere all the time, they gain a better overall understanding of how ecosystems are changing using data collected by citizen scientists.

Citizen science is not new. Since the beginning of time, people have studied and documented nature’s events to understand her cues. Did you know Thomas Jefferson was a citizen scientist? He kept detailed records about when plants in his garden at Monticello bloomed and fruited. Henry David Thoreau was also a citizen scientist. He carefully observed and recorded the workings of nature for many years on Walden Pond.

The good news is that you don’t have to be Thomas Jefferson or Henry David Thoreau to be a citizen scientist. It is for anyone who is curious about how nature works. You can participate in your own backyard. Children can get involved too. Also, you don’t need to grow any fancy plant specimens or live on a nature preserve to make contributions. Nature is in action all around us – no matter where we live.

By getting involved in a citizen science program you can add scientific observations to an existing body of data. You can also formulate your own scientific questions, investigations, and interpretations. There are many citizen science organizations to get involved with, but I decided to delve into a program called Nature’s Notebook.

Nature’s Notebook, created and maintained by the National Phenology Network (NPN), is an online interface used for observing and recording plant and animal phenology changes. What in the world, you may ask, is phenology? I asked the same question when I first heard this term after a speaker from the Science Museum of Virginia mentioned it in a presentation at an American Public Garden Association Education Conference a few years ago.

I learned that phenology is nature’s calendar. It is a critical component of life on Earth. It gives us information about when daffodils bloom in the spring, when tadpoles transform into frogs and when birds begin their fall migration to warmer climates. By studying these types of natural lifecycle events in relationship to shifting weather patterns, we can learn how ecosystems are adapting to our changing world. It is helpful to study phenology over long periods of time to get a sense of the big picture. The timing of some changes in plant and animal lifecycles happens very slowly, but some occur more rapidly. Either can cause disruptions in ecosystem balance. For example, if a species of caterpillars hatch earlier than usual one spring, they might turn into moths before a species of bird that needs those particular caterpillars as a food source migrates back to its seasonal home.

I was intrigued. I decided to take a NPN course that would certify me to be a local phenology leader. The course was rigorous for sure, but just like a butterfly emerges from a chrysalis, I emerged with a new awareness of the amazing changes happening in nature, all around me, every single day, even in my own backyard.

What to Observe

When I first began trying to use the Nature’s Notebook program, I was a bit overwhelmed because there are so many choices of plants and animals to observe. Squirrels scamper around my backyard. A young redbud tree with heart-shaped leaves grows at the front of my home. There is a huge old oak tree in the side yard. Bees are buzzing around all over the place. There are over a thousand species to choose to observe in Nature’s Notebook database. But I learned, it doesn’t really matter where you start. Starting is the important part.

Why not start with a plant that you have easy and regular access to. It should be a plant that you can observe at least once a week, over at least a full growing season. If you can continue your observations for more than a calendar year, the data you contribute is more meaningful.

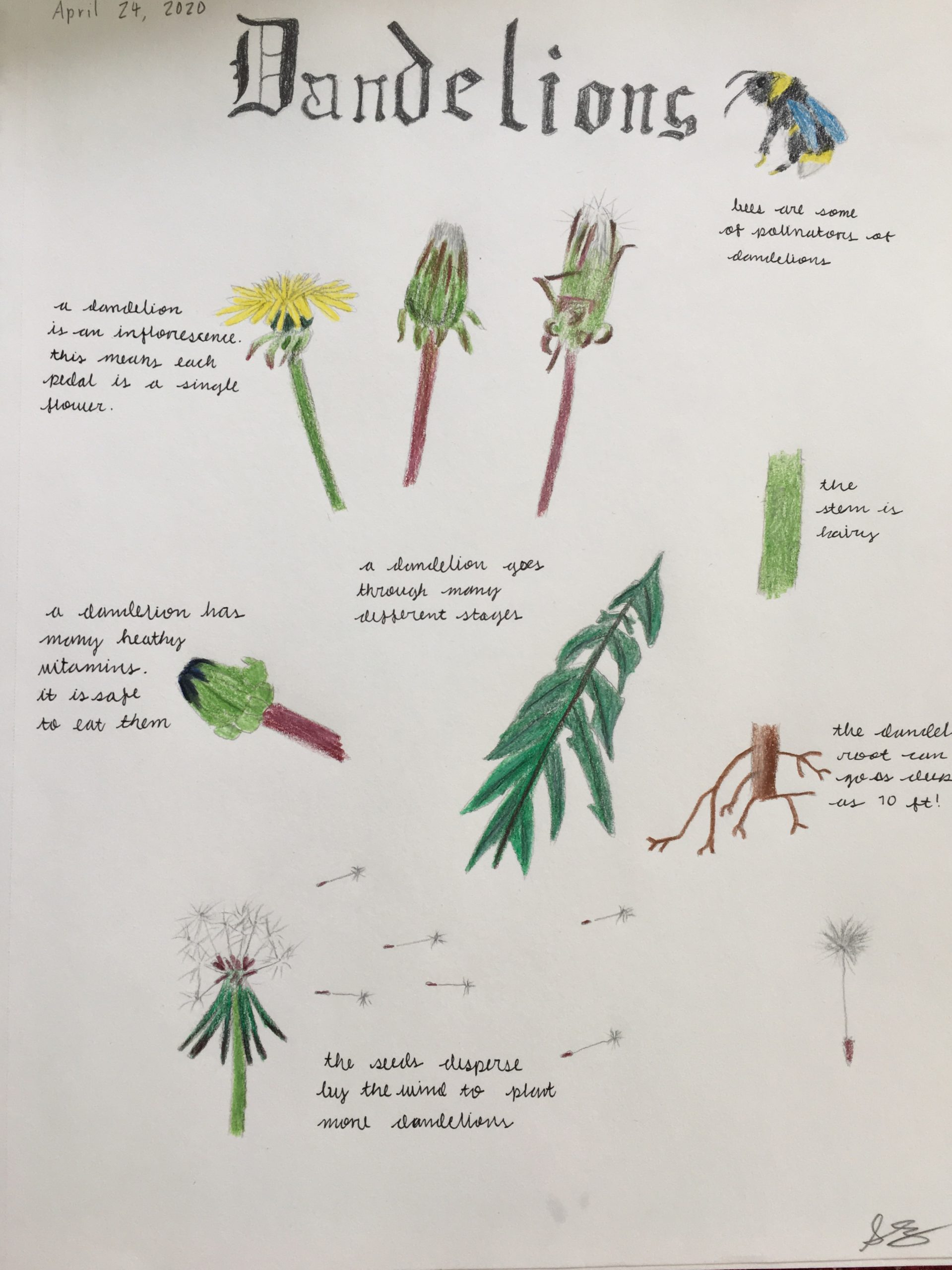

I recommend starting with a weed. What? How boring, you might say. I sort of thought that at first too, but once you start to really observe weeds, you just might find that they become the opposite of boring. Weeds are easy to find, and they move quickly through phenophases (lifecycle changes). You don’t have to wait long to see their amazing transformations. Dandelions, white clover, and blue violets are all likely to be growing in your backyard, and they are all on Nature’s Notebook list of plants with scientifically vetted observation protocols. When plants are small, like these “weeds,” Nature’s Notebook recommends observing a designated small patch rather than just a single plant. Just try not to mow over them while you are observing them. If you don’t want to start with observing a weed, that’s ok. There are lots of other plants and animals to choose from on Nature’s Notebook species list.

How to Start Making Observations

- Sign up for a new account at USANPN.org

- Review observation directions from the species list about how to observe your chosen plant or animal species. Observations of all species involve documenting the phenophases. For example, you would document if plants are sprouting, leafing out, budding, fruiting, or going dormant. Nature’s Notebook observation protocols have been standardized and scientifically vetted in order to make the data as meaningful as possible.

- Prepare to record data by printing out datasheets for your chosen species. You can transfer the data online later if you prefer.

- You can also choose to download the Nature’s Notebook mobile application. If you use the app, there is no need to print out the datasheets.

- Whenever you get stuck, refer to How to Observe, Nature’s Notebook Plant and Animal Phenology Handbook (PDF).

What Happens to the Data I Collect? How Can I Stay Involved?

- Look to see how your observations fit into a national body of data by using the USA-NPN visualization tool. This tool allows you to explore phenology data. You can choose from several types of visualizations including maps, scatterplots, activity curves and calendars.

- Develop scientific questions and study your data to try to find the answers. Examples of scientific questions might be: Under what conditions do wild violets thrive? How fast do dandelions reproduce in a certain area? If you want to add an insect observation, you could ask: How many bumblebees visit a patch of white clover over a certain period of time.

- Do further scientific investigation by studying multiple specimens — or study plants in different locations. This could be a science project for kids and families to enjoy.

- While making your observations, take the time to do some nature journaling. Here’s a guide to get started from John Muir Laws, or if you are looking to the future we some great nature journaling classes here at Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden that we hope to offer again soon.

- Practice your nature photography by taking pictures of the various lifecycle stages of the specimens you are observing.

- Learn about recent phenology research. Perhaps the species you are observing has been involved in a research study. How wonderful would it be to see your observations leading to an important scientific discovery! Together our data is meaningful.

You can see the results of critical citizen science work and how it affects your local community by entering your zip code in the visualization tool. See these interactive graphics and more: