The Mighty Oak Tree

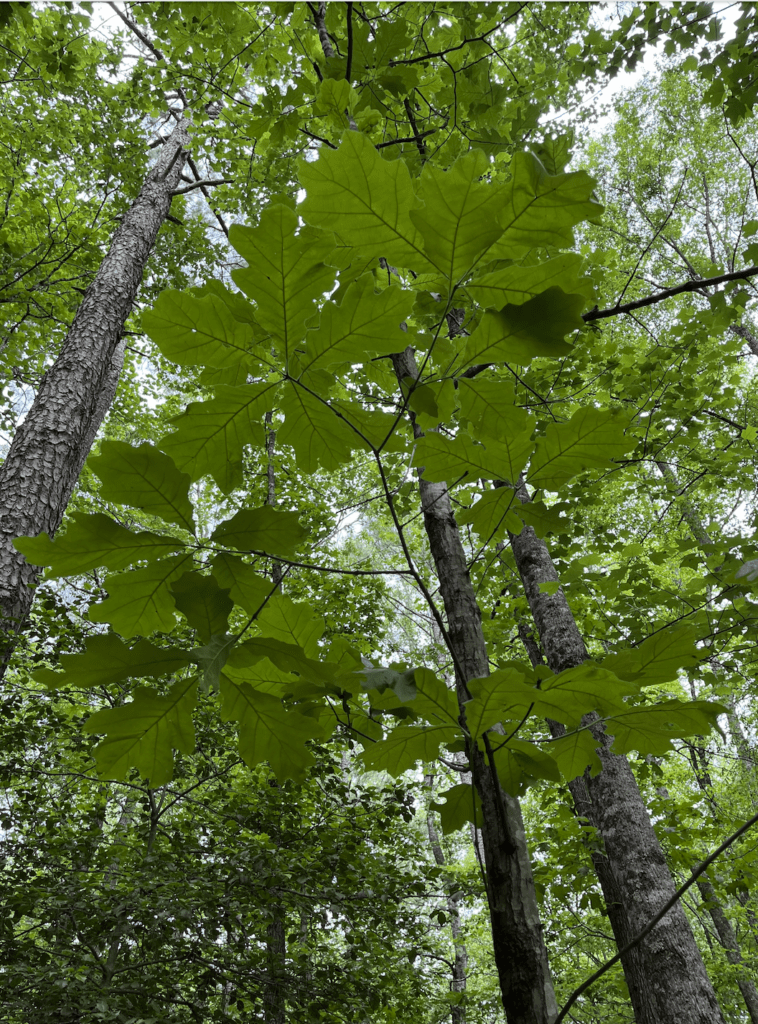

The branches of Lewis Ginter’s Darlington Oak, planted in 1987, stretch across Grace Arents Garden (photo by Tom Hennessy)

At the apex of every arch, a keystone is laid. Large, wedge-shaped, usually proud and often embellished, its role might seem ornamental; in truth it is monumental. A keystone locks all of the stones of an arch in place, stabilizing the structure and enabling it to bear weight. Without a keystone, an arch will fall.

When nature engineers an ecosystem, she sets her own keystones. She lays down a network of interdependent relationships, cementing plants, animals and insects in place with the ecological services that they unwittingly offer each other daily. Bees pollinate plants, oyster reefs filter water, earthworms aerate soil, birds scatter seed. Each one contributes; everyone benefits. When a particular member species offers a significant number of life-sustaining ecological services, we call it a keystone species. Like its architectural namesake, the weight of its contribution helps to strengthen and stabilize the entire ecosystem.

Mighty and Magnificent

The mighty oak is one of the most generous of our keystone species. Oak trees purify more air, filter more water, stabilize more soil and provide more food and habitat for local wildlife than many tree species. Research published by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in 2019 revealed that 2,300 species worldwide are supported by oak trees. Also, 326 species depend on oaks for survival and 229 species are rarely found on trees other than oaks.

In just 20 years, a Quercus alba, or white oak, will mature to a height of 65-85 feet with a canopy spread of almost the same width. Although their average life expectancy is 150-300 years, it is not uncommon for a white oak to live for as long as 400 years. Some have been known to live for over 1,000 years – all in faithful service to their respective ecosystems.

In the US, about 75% of the insects that birds require for food depend on “keystone plants” like oaks, cherries, willows, birches, hickory pine and maple, according to The Nature of Oaks. (photo by Susan Higgins)

What Makes Them So Magical?

Dr. Douglas W. Tallamy, Chairman of the Department of Entomology at the University of Delaware, wrote a book about these leafy servant leaders. The Nature of Oaks is an ode to the oak tree, a month-by-month exploration of the many ways that oak trees, “Support more forms of life and more fascinating interactions than any other tree genus in North America.” Here’s how:

Soil Stabilization

Oaks are the super-heroes of soil stabilization. Their shallow root systems can extend as far as three times the width of their crown spread. This forms a massive mesh that secures soil particles in place, helping to conserve soil and prevent erosion.

Watershed Management

When it rains, that same broad network of roots steps in to strain stormwater. This prevents sediment from entering waterways and filters excess nitrogen and phosphorus from the soil. The roots also absorb rainwater, helping to reduce flooding downstream.

Water Purification

On the ground, a thick mat of oak leaf litter can soak rain up like a sponge. Stalling the flow of stormwater for long enough allows it to seep into the soil and replenish the groundwater below. Without it, runoff from a 2-inch rainstorm could cause a flood. Oak leaves are also loaded with lignins and tannins which slow decomposition, prolonging their ability to intercept rainfall, recharge groundwater and reduce flooding and erosion.

The canopy of single mature oak can intercept up to 40,000 gallons of water annually, breaking the force of heavy rain before it reaches the ground. (photo by Susan Higgins)

Climate Moderation

Above ground, the massive canopy of an oak helps to moderate the local micro-climate year-round. By buffering wind, casting shade in the summer, and radiating warmth in the winter through passive solar gain, the climate is protected.

Wildlife Nourishment

Wildlife feed on almost every part of an oak tree, from its flowers, seeds and leaves to its bark and roots. More than 100 species of vertebrate animals consume acorns in the U.S. This includes mammals such as white-tailed deer, gray squirrels, fox squirrels, flying squirrels, mice, bear, voles, rabbits, raccoons, opossums, gray foxes, red foxes, and wild hogs. Birds that feed on acorns include wild turkey, bobwhite quail, wood ducks, mallards, woodpeckers, crows, and jays. Oak flowers are food for both red and gray squirrels and many insects, while bees consume oak pollen.

Wildlife Habitat

Because they decay very slowly, the 700,000 leaves that fall from a single mature oak in one season can provide housing, food and moisture for insects and small animals for up to three years. Snug in the cavities and deadwood of an oak tree, birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and insects find shelter from weather, additionally finding places to rest and reproduce. Many moth species spend the winter in the caterpillar stage, hiding on small branches and in the bark. Oaks also support 108 different types of fungi, 57 of which depend on them exclusively as well as 700 types of lichen whose many shapes, colors and sizes offer nesting material, food and shelter for other wildlife.

Pollinator Hosts

An oak tree will host an astounding 534 different species of pollinators, compared to poplar trees which host 368 and maples which host 285. (The Nature of Oaks)

“It is now within the power of individual gardeners to do something that we all dream of doing: to make a difference. In this case, the difference will be to the future of biodiversity, to the native plants and animals of North America and the ecosystems that sustain them,” Tallamy says in The Nature of Oaks. “If you are at all interested in contributing to the conservation of local animals, or in enjoying the wonders of nature right at home, planting one or more oaks is an awfully good way to do those things.”