Oriental Bittersweet: A “Dirty Dozen” Plant

This week’s Dirty Dozen plant is oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus). Since it is still available in the horticultural trade, we hope that the following information will convince you not to buy this plant.

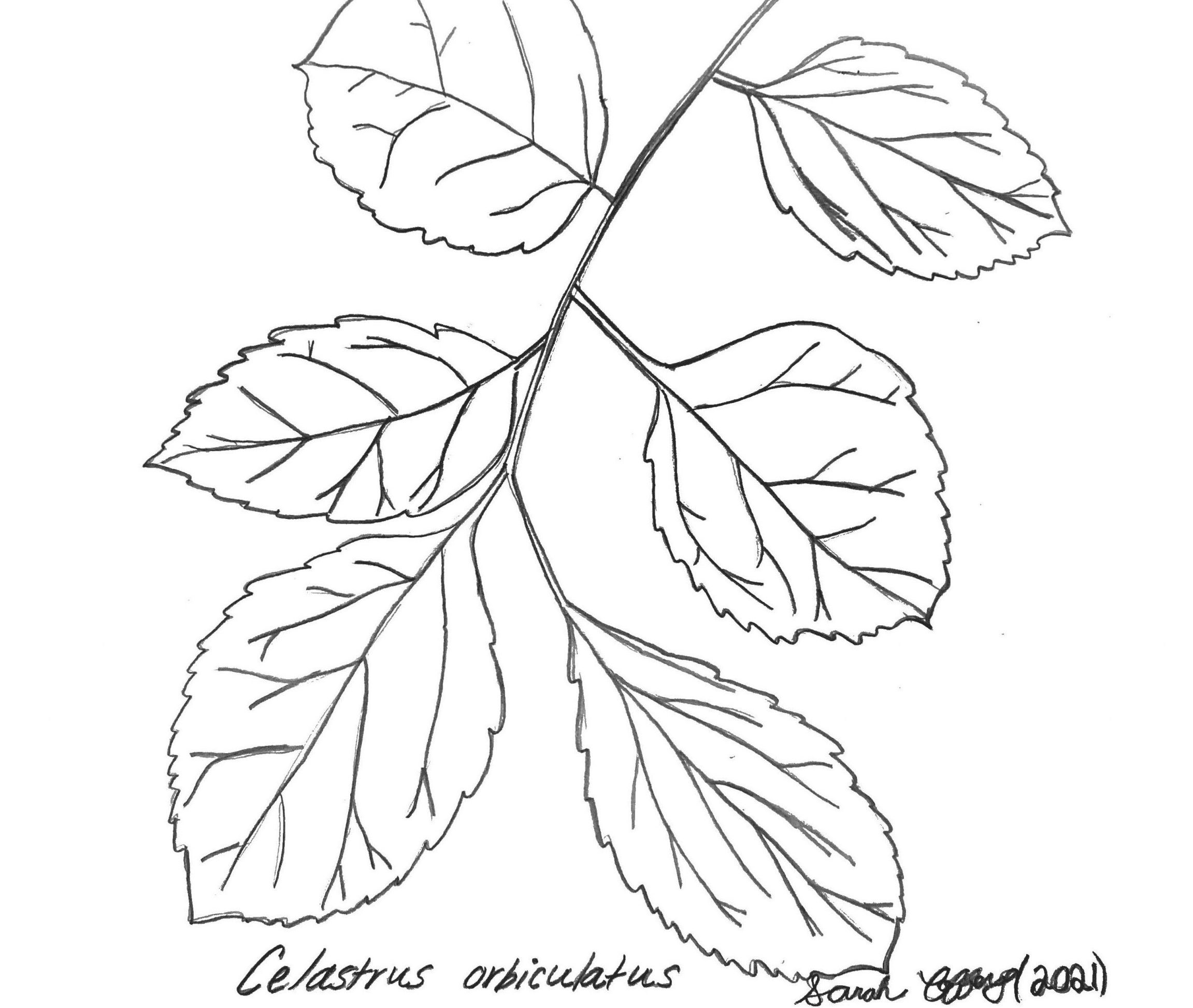

In this sketch, you can see that oriental bittersweet leaves are round with toothed edges. Drawing by Sarah Coffey.

Oriental Bittersweet

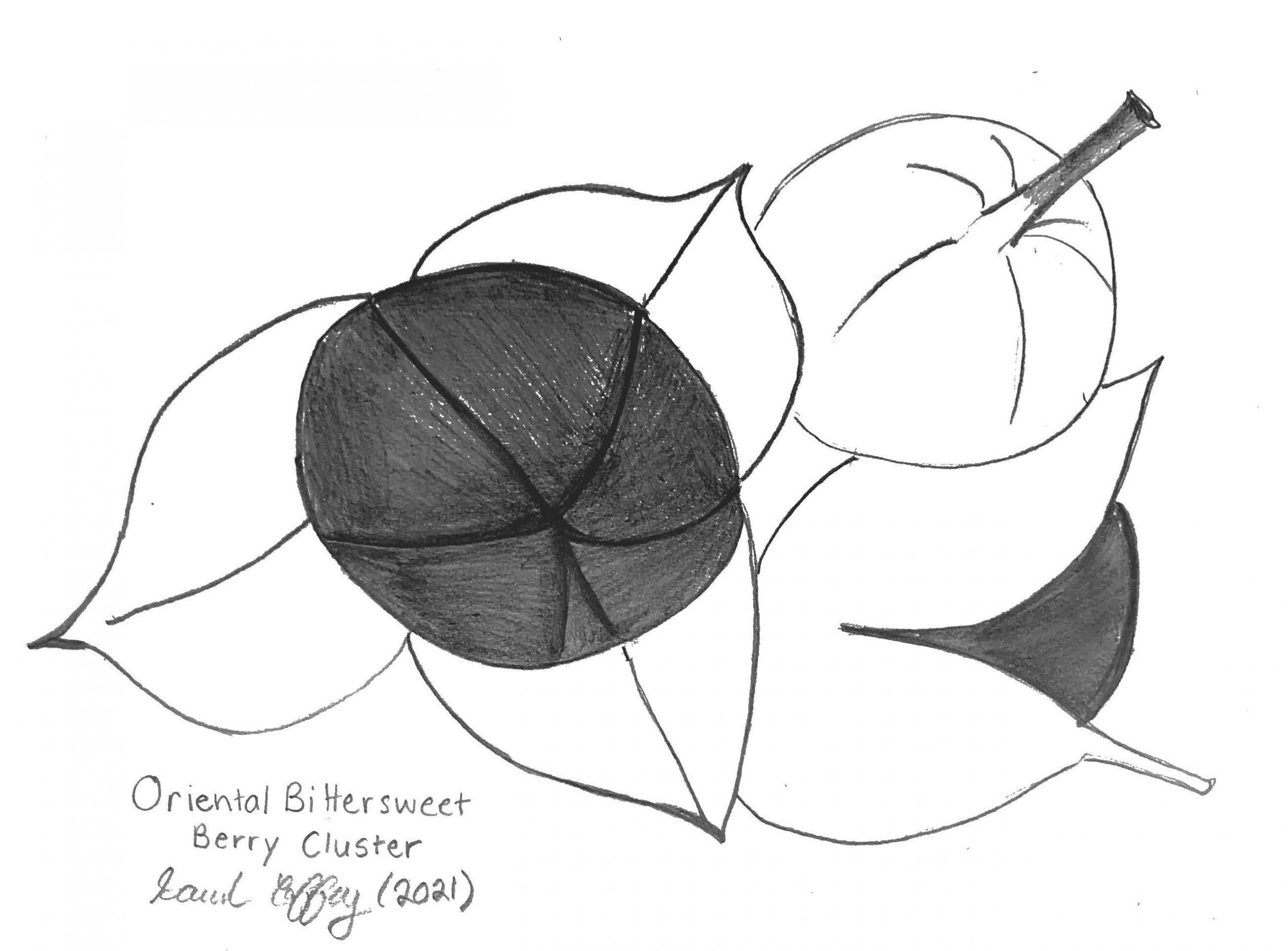

Celastrus orbiculatus is a member of the bittersweet family (Celastraceae). This deciduous, perennial, woody vine can grow up to 60 feet tall (about twice the height of a telephone pole) and 10 inches in diameter. Its round or elliptical-shaped leaves are usually 3-4 inches in length. Oriental bittersweet is dioecious, meaning that pollen and fruits come from separate male and female plants, as opposed to monoecious plants, which have both male and female flowers on the same individual. Fruits have yellow skins that peel back in the fall and reveal bright red berries. These berries remain in the winter after foliage has dropped.

Oriental bittersweet berries are bright red with yellow skins. The top right berry’s skin has not yet split. Drawing by Sarah Coffey.

How Did it Get Here?

In 1860, oriental bittersweet was introduced to the United States as an ornamental plant. It is native to Korea, Japan and China.

Where is it Found?

Geographic Region: C. orbiculatus is listed as a high-risk invasive species (PDF) for all of Virginia. This map shows that oriental bittersweet has invaded most of the Northeast and the Midwest United States.

Habitat: A range of environments is suitable for oriental bittersweet to thrive, from alluvial woodlands (that is, forested areas near streams), to thickets and roadsides (PDF). Full sun is preferable, and seedlings in shaded areas will climb trees and shrubs as they develop to gain better light access.

What is the Impact of Oriental Bittersweet on the Environment?

The greatest danger of C. orbiculatus invasions is its ability to hybridize with American bittersweet. Hybridization is the interbreeding of two plants that are genetically different either because they are from different taxa or different populations. This can actually increase the invasiveness (PDF) of a plant by improving its ability to adapt in areas where it is introduced. Invasive hybrids may become so successful that the genetic identity of natives (which in this case would be C. scandens) becomes lost. In other words, they can lead native species to extinction! Like other invasive vines, C. orbiculatus outcompetes native vegetation. If left unchecked, it can strangle and kill large trees.

What Options Exist for Controlling Oriental Bittersweet?

C. orbiculatus can be confused with American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens), so before removing it, be sure you haven’t stumbled upon a patch of our native bittersweet. Tips for distinguishing the two are found on pages 24-25 of Mistaken Identity?: Invasive Plants and Their Native Look-Alikes (PDF). All sightings of oriental bittersweet should be reported to the Virginia Invasive Species Working Group.

Because both oriental bittersweet and porcelain berry are perennial, woody, deciduous vines, removal methods are nearly identical. We recommend reading our blog post on porcelain berry for the best control strategies (mechanical and/or chemical). For more tips, please read Penn State Extension’s page on C. orbiculatus.

What are Native Substitutes?

If you like the way oriental bittersweet looks but want to plant something that is native to Virginia’s Capital Region (Richmond), we recommend the following alternatives: strawberry bush (Euonymus americanus), winterberry holly (Ilex verticillata), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquifolia) and trumpet or coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). It also never hurts to plant our native bittersweet C. scandens, whose natural populations are currently dwindling.

Want to Know More?

For more information, check out Invasive Alien Species of Virginia (PDF) and the USDA National Invasive Species Information Center.